Monthly Post

Well.

I had intended to be writing this post over a month ago, but [for reasons] I’m here writing it now.

Way back in March of ‘25, I was doing work that I could talk about publicly, and a sizable chunk of that was working to improve Gallium. The stopping point of that work was the colossal !34054, which roughly amounts to “remove a single * from a struct”. The result was rewriting every driver and frontend in the tree to varying extents:

` 260 files changed, 2179 insertions(+), 2331 deletions(-)`

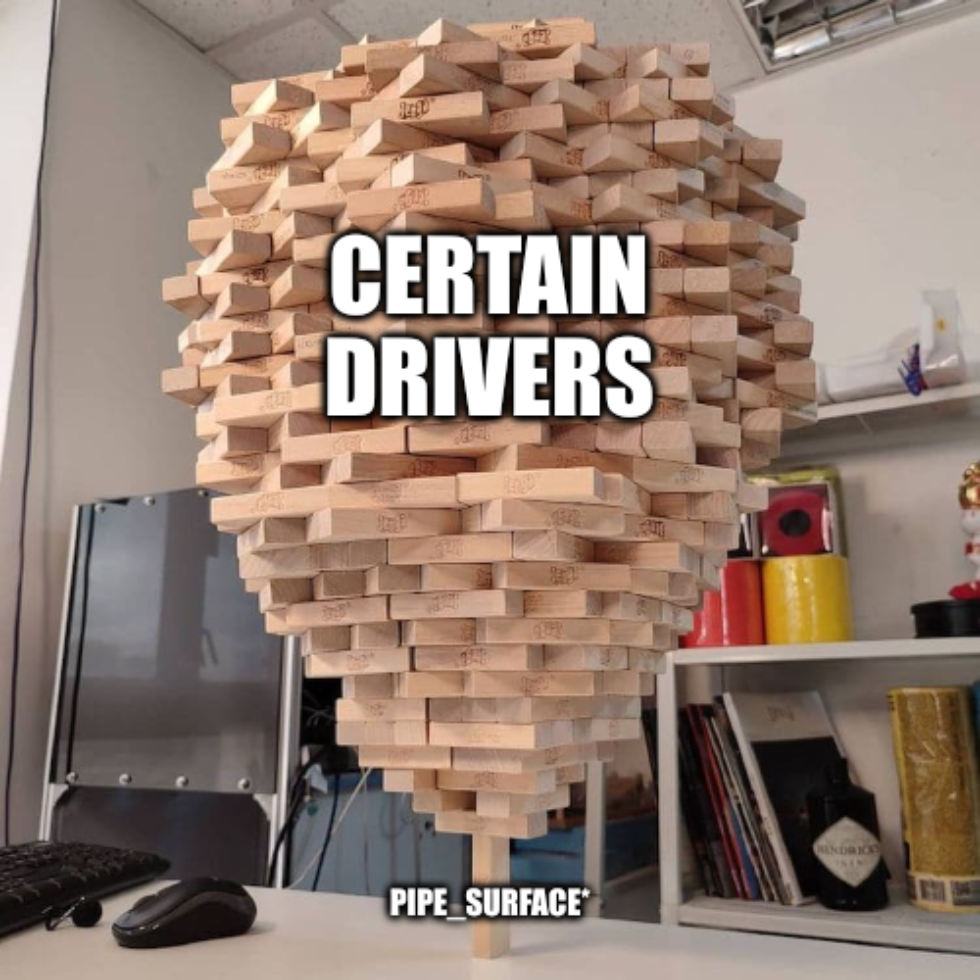

So as I was saying, I expected to merge this right after the 25.1 branchpoint back around mid-April, which would have allowed me to keep my train of thought and momentum. Sadly this did not come to pass, and as a result I’ve forgotten most of the key points of that blog post (and related memes). But I still have this:

But Hwhy?

As readers of this blog, you’re all very smart. You can smell bullshit a country mile away. That’s why I’m going to treat you like the intelligent rhinoceroses you are and tell you right now that I no longer have any of the performance statistics I’d gathered for this post. We’re all gonna have to go on vibes and #TrustMeBuddy energy. I’ll begin by posing a hypothetical to you.

Suppose you’re running a complex application. Suppose this application has threads which share data. Now suppose you’re running this on an AMD CPU. What is your most immediate, significant performance concern?

If you said atomic operations, you are probably me from way back in February–Take that time machine and get back where you belong. The problems are not fixed.

AMD CPUs are bad with atomic operations. It’s a feature. No, I will not go into more detail; months have passed since I read all those dissertations, and I can’t remember what I ate for breakfast an hour ago. #TrustMeBuddy.

I know what you’re thinking. Mike, why aren’t you just pinning your threads?

Well, you incredibly handsome reader, the thing is thread pinning is a lie. You can pin threads by setting their affinity to keep them on the same CCX, and L3 cache, and blah blah blah, and even when you do that sometimes it has absolutely zero fucking effect and your fps is still 6. There is no explanation. PhDs who work on atomic operations in compilers cannot explain this. The dark lord Yog-Sothoth cowers in fear when pressed for details. Even tariffs on performance penalties cannot mitigate this issue.

In that sense, when you have your complex threadful application which uses atomic operations on an AMD CPU, and when you want to achieve the same performance it can have for free on a different type of CPU, you have four options:

- pray that CPUs, kernels, and compilers improve to the extent that the problem eventually goes away on its own

- stop using AMD CPUs

- stop using threads

- stop using atomic operations

Obviously none of these options are very appealing. If you have a complex application, you need threads, you need your AMD CPU with its bazillion cores, you need atomic operations, and, being realistic, the situation here with hardware/kernel/compiler is not going to improve before AI takes over my job and I quit to become a full-time novel writer in the budding rom-pixel-com genre.

While eliminating all atomic operations isn’t viable, eliminating a certain class of them is theoretically possible. I’m talking, of course, about reference counting, the means by which C developers LARP as Java developers.

In Mesa, nearly every object is reference counted, especially the ones which have no need for garbage collection. Haters will scream REWRITE IT IN RUST, but I’m not going to do that until someone finally rewrites the GLSL compiler in Rust to kick off the project. That’s right, I’m talking to all you rustaceans out there: do something useful for once instead of rewriting things that aren’t the best graphics stack on the planet.

A great example of this reference counting overreliance was sampler views, which I took a hatchet to some months ago. This is a context-specific object which has a clear ownership pattern. Why was it reference counted? Science cannot explain this, but psychologists will tell you that engineers will always follow existing development patterns without question regardless of how non-performant they may be. Don’t read any zink code to find examples. #TrustMeBuddy.

Sampler views were a relatively easy pickup, more like a proof of concept to see if the path was viable. Upon succeeding, I immediately rushed to the hardest possible task: the framebuffer. Framebuffer surfaces can be shared between contexts, which makes them extra annoying to solve in this case. For that reason, the solution was not to try a similar approach, it was to step back and analyze the usage and ownership pattern.

Why pipe_surface*?

Originally the pipe_surface object was used solely for framebuffers, but this concept has since metastacized to clear operations and even video. It’s a useful object at a technical level: it provides a resource, format, miplevel, and layers. But does it really need to be an object?

Deeper analysis said no: the vast majority of drivers didn’t use this for anything special, and few drivers invested into architecture based on this being an actual object vs just having the state available. The majority of usage was pointlessly passing the object around because the caller handed it off to another function.

Of course, in the process of this analysis, I noted that zink was one of the heaviest investors into pipe_surface*. Pour one out for my past decision-making process. But I pulled myself up by my bootstraps, and I rewrote every driver and every frontend, and now whenever the framebuffer changes there are at least num_attachments * (frontend_thread + tc_thread + driver_thread) fewer atomic operations.

More Work

This saga is not over. There’s still base buffers and images to go, which is where a huge amount of performance is lost if you are hitting an affected codepath. Ideally those changes will be smaller and more concentrated than the framebuffer refactor.

Ideally I will find time for it.

#TrustMeBuddy.